Nejnovější

Nejčtenější

Hlavní strana » English Pages » Czechoslovakia and the Czech…

Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic - The Spirit and Main Contours of the Postcommunist Transformation

English Pages, 24. 11. 2014

The topic “a quarter of a century after the transition from communism” is very relevant and deserves to be openly and seriously discussed. We policy makers very strongly believe that, in the context of developments in both our own countries and in Europe overall.

The topic “a quarter of a century after the transition from communism” is very relevant and deserves to be openly and seriously discussed. We policy makers very strongly believe that, in the context of developments in both our own countries and in Europe overall.

I have a personal interest in keeping alive awareness, as well as understanding, of the unique era of the fall of communism (and, in many respects, of its unrepeatable tasks).[1] I have several reasons for wanting to do so. The desire to be understood is only one of them. I also have a sense of historical duty and responsibility toward the people who were actively involved in the historic transformation process in my country more than two decades ago.

The Czech experience suggests that there is no end to history and that countries may be confronted with similar challenges in the future. Europe in particular needs not cosmetic, superficial, and partial measures (like the ones being proposed and sometimes even implemented) but deep, fundamental systemic change. Europe’s problems are not accidental; they are deeply rooted in its political and economic systems. Those of us who have experience and knowledge of systemic change should continue stressing the need for such change again and again in all kinds of European political debates.

A further motivation for returning to the events connected with the fall of communism is to resist the process of very harmful forgetting, which, regretfully, cannot be avoided. Policy makers are already one generation away from the postcommunist transition.[2] Our assistants and younger colleagues were starting primary school at that time; they have no direct knowledge of the events of that era. The ongoing political disputes (which reflect the Orwellian dictum that he who controls the past controls the present, he who controls the present controls the future) also make proper understanding of that era more and more difficult, if not impossible. Those disputes are based on a caricature of that unique and historic process of change rather than on facts.

Indeed, many details have already been irretrievably forgotten, only some of them quite rightly. Some of the controversial issues have ceased to be so and are now accepted and taken for granted. It is difficult to understand why they roused such emotions 20 years ago.

Some dangerous misinterpretations, however, continue to exist, and we, the reformers of our time, should try to correct them. Their continuation partly reflects, or at least was made possible by, the absence of serious theoretical contributions to this topic, as well as by an inability and desire to generalize.

We policy makers should accept part of the blame. In the past we mostly stressed the differences, not the similarities, between our countries. We emphasized the originality of reforms (and reformers!) in a country without trying to see the common denominator of what at first sight seemed to be very diverse experiences and procedures (often only because of different terminology). I have the feeling that the reforms in various postcommunist countries had more in common than is usually admitted. We now have an opportunity to do something about the misinterpretations, whereas it will be almost impossible to do so in another 10 years’ time.

The topic of transition – or systemic change – is wide and multidimensional. Some restrictions on the scope of this discussion are therefore necessary. I touch solely on the political and economic aspects of the transition throughout the region. Therefore I deal just with the relatively short period between the fall of communism and the beginning of transformation on the one hand and the nonrevolutionary developments in the much longer posttransformation era on the other (lasting, of course, different times in different countries).

I often use a medical analogy to explain the issues we reformers faced. Consider a doctor who is thinking about how to treat a patient: when to perform surgery, how long a period of convalescence to impose, and how long a period of normal but cautious activity to prescribe after convalescence (including nutrition and fitness programs). I therefore discuss transformation, not posttransformation. The transformation process inevitably created new, very fragile societies and fragile political and economic systems that needed a chance for long-term evolutionary development (discussion of this phase is a topic for a different book).

At the moment of transition, my country also went through another radical change: Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia (see 2014a). The transformation process took place in large part in the common state, Czechoslovakia, or was at least based on a common scheme. What was different was the post-Czechoslovak transformation era. Before the split there were disputes between Czechs and Slovaks about transformation – indeed, these differences were part of the reason for the split. But the legislation in the era of transformation – that is, the official document of the transformation process, the Scénár ekonomické reformy (Scenario for Economic Reform) – was approved by the federal parliament in September 1990, when Czechs and Slovaks did not envisage the split of their country, and so it was identical for each side.

Intellectual Background and Main Conceptual Ideas of the Czech Reformers

A relatively small group of academic economists – most of whom knew one another in the last years of communism and who had ideas that were formed long before the fall of communism – led the radical economic transformation of Czechoslovakia. The group’s older members had started thinking about reform in the 1960s, at the time of the rather radical Czechoslovak Economic Reform (which culminated in the Prague Spring of 1968); the younger members had begun thinking about reform in the frustrating period of nonreforms in the 1970s and 1980s. Most of the reformers were Czechs; Slovak economists played a much smaller role.

What were the main features of our thinking in those days?

- We took for granted the need to totally and unconditionally liquidate the communist political and economic system – we took this idea as our starting point. In previous years some of us had engaged in very critical analysis of the late communist system, which was a good basis for our thinking. We were in frequent contact with our academic colleagues in other Central European countries, especially Poland and Hungary.

- We interpreted the old system rather unconventionally, not as a textbooklike centrally planned economy but as a centrally administered, heavily distorted market economy (Klaus 2009). Regretfully, research of this nature was interrupted by and forgotten after the fall of communism. This way of thinking significantly influenced our approaches to the transformation challenge.

- We were aware – together with Friedrich von Hayek and the whole Austrian School of economics – that it was not possible to create and change a complex system by means of politically organized procedures. Such a change had to happen in an evolutionary way. We understood that the transformation process had to be a mixture of constructivism and spontaneous evolution. We knew that transformation was not an exercise in applied economics and that theories of “optimal sequencing of reform measures,” so popular with economic theoreticians, were of very limited use.

- Above all we wanted to avoid a nontransformation – that is, postponement of its beginning, the unnecessary compilation of comprehensive blueprints for reform, long unproductive debates about the details of future decision making, and so forth. Speed was crucial for us. We did not want to allow opportunities for all kinds of rent-seeking groups to try to preserve the status quo or hijack the whole transformation process to benefit their own vested interests. We did not want to give the opponents of reform time to organize and block change. Therefore we opposed all versions of gradualism, which we considered a nonreform. Gradualism was the politically correct path to transformation, but it was absolutely the wrong approach.

- Explicitly and very early on we proclaimed that we wanted capitalism. We were not afraid of using that term. We lived in the country of Ota Šik, the main Czechoslovak reformer of the 1960s, who later became one of the main exponents of the ideology of the so-called third way. He returned from Switzerland a few days after the Velvet Revolution. We met with him then and told him “No” – we were not interested in any kind of third way; we were already a generation ahead. He accepted our decision in a friendly manner and returned to St. Gallen without interfering in our reform plans, something we acknowledge even now, two decades later.

- We knew that successful transformation must fulfill three basic preconditions: (a) present a simple, clearly formulated positive vision of where to go; (b) demonstrate our knowledge of how to get there; and (c) prove our ability to sell both to the public.

- We considered radical reform the only way to avoid chaos, instability, and political turmoil and to obtain at least the basic support of our fellow citizens.

- We believed that the transformation project had to be ours, based on our ideas and our realities. We knew there was no reason to import the concept of transformation or new institutions, including legislation (as East Germany did). We also knew that the whole project had to be put together by means of a democratic process at home, that there was no perfect model, that no model of a complex system was importable (unified Germany being an exception), and that importing a model would lead to an unbearable increase in transformation costs (as happened in East Germany).

- We did not consider ourselves representatives of any international institutions, and we did not feel the need to please these institutions or their representatives.[3] We tried to find our own “Czech way.” We sought to maximize the number of voters at home, not get a pat on the back in Washington. When it came to the distribution of transformation costs and benefits in our society, we had our own views and priorities. These views were inevitably different from those of our foreign advisors and potential foreign investors. Selling out the country abroad at the time of transition was politically unacceptable, and we reformers considered it wrong. We wanted to give the people the chance to be part of the game, not just passive observers. This notion significantly influenced our concept of privatization (and other reforms).

- We considered economic and political reforms interconnected and indivisible. Separating them the way China did or masterminding the sequencing of economic reforms (as Joseph Stiglitz and his colleagues repeatedly suggested) was impossible. The political changes began very rapidly, almost immediately (the only necessary precondition was the liberalization of entry into the political market); the economic changes followed shortly thereafter. The whole concept of gradualism was (and is) based on the belief that reforms can be meticulously orchestrated. Gradualism would have been possible only in the absence of political freedom, which was not the case in our country. We were prime ministers, not czars.[4]

Our opponents did not present an alternative transformation concept. To be fair, they were at a disadvantage. Citizens wanted radical change, and we succeeded in convincing them that our views represented change. Our opponents were not unified and lacked a strong common idea. They limited themselves to issuing warnings about inflation, unemployment, the selling of the “family silver,” the dominance of foreign firms. They had just one standard argument that had its roots not only in communism but also in current social democracy: Do not believe in the market, do believe in the inevitably important role of government in organizing the economy. We were accused of being Chicago boys or Hayekians, of being antisocial, of being economically “narrow minded,” of attempting to introduce Dickensian 19th century capitalism. It was relatively easy to demonstrate the irrationality of such accusations – and luckily events proved us right.[5]

Outline of Our Transformation Concept

We wanted to accomplish rapid transformation, rapid systemic change. We resolutely refused all those dreams about third ways or the convergence of economic and political systems that were so fashionable in the West in previous decades. We consistently refused to accept “shock therapy” and “gradualism” as meaningful and competing alternatives (Klaus 2014b). We did not believe that gradualism was a realizable reform strategy (in a full-fledged democracy), and we disagreed with the term shock therapy as either a useful reform concept or a description of the reality in our country or elsewhere (see Klaus 2013b).[6]

Time was a very important factor in the success of reforms, for many reasons. We needed relatively fast results. We did not want to give the opponents of transformation an opportunity to assemble wide political support. We also knew that slow and only partial reforms would create new distortions and imbalances. We wanted to maintain momentum. But high-speed therapy does not mean shock therapy. We explained all the reforms step by step to the public in advance so that the reforms would hold no surprises for them. Even though we placed all of our stress on speed, we looked very carefully at social consequences. Our refusal to use the term social market economy did not (and does not) mean that we did not pay close attention to the appropriate social policy.

Various reform measures had very different time requirements. Some of them (often the most radical ones, such as price liberalization) needed only to be announced and they began to function immediately (the consequences, of course, occurred with a time lag). Other measures – privatization, legislation, institution building – took months or years to be fully adopted and implemented. Some of them were in the hands of government administrations, but most of them required a lengthy parliamentary procedure. Some were known ex ante; others were discovered “on the way.” The debate about shock therapy and gradualism misses this complexity.

Let’s just call a wrong therapy a wrong therapy, not a shock therapy. We always argued against the sophisticated masterminding of reforms (as an antidemocratic procedure), but we understood that some rules existed and had to be followed and respected. Liberalizing prices (and wages) without first gaining control over the macroeconomic situation was the wrong therapy. Some countries applied it, ours did not. We were fully aware of these rules in advance.

Liberalizing prices without a parallel liberalization of foreign trade would have been a tragic mistake in a small economy. We liberalized both the same day (January 1, 1991). But we reformers were ready to accept that in big economies such as Russia or China this simultaneity was not so important. The economies of smaller countries had a more monopolistic structure. We needed to liberalize prices before we could privatize and restructure industries and firms. Postponement of price liberalization would have been detrimental.

Many disputes were (and continue to be) centered on the issue of whether it is obligatory to have in place an institutional framework for a market economy before deregulating its markets and beginning privatization. This debate has persisted through time, but it is a dialogue of the deaf.

Those on one side of the dispute keep reminding those of us on the other side of the elementary truth that institutions (in a broad sense, including legislation) are important. They set us up as straw men who disagree with this view, which is, of course, nonsense. All of us are in favor of having in place institutions that are as perfect as possible as quickly as possible.

The dispute is about something else. It is about whether (and to what extent) to delay other aspects of the transformation process if institutions are not yet perfect or at least not sufficient. The Czech experience reveals the following:

- Halting deregulation, liberalization, desubsidization, and privatization would have been practically impossible.

- Even if it had been possible, the costs (connected with the demise of the old communist institutions, especially the disappearance of central planning) would have been enormous. The disappointment of people who had only just gained their freedom would have been impossible to ignore.

- Institution building is an endless task and takes time. Day by day, without interruption, reformers built institutions in all the transforming countries. They did so despite a difficult parliamentary process, the significant involvement of trade unions and other nongovernmental organizations, and an ultimately free but uncooperative media. We prepared hundreds of new pieces of legislation. Our capacity for law making was certainly not perfect, and lawyers did not help us much, because they did not have the reform mentality needed; they were status quo keepers.

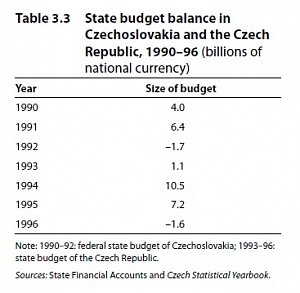

Given our goals, our inherited realities, and our relative political strengths, we adopted a very simple scheme that more or less indicated the sequencing of our transformation process. First, we were aware of the enormous importance of at least relative macroeconomic stability to the success of transformation. We were in charge of the crucial institution, the Ministry of Finance, which made it possible to send a strong signal in this respect at the very beginning. We succeeded in rapidly correcting the state budget that had been prepared by the old perestroika-type government for the first transformation year. We visibly cut government expenditures and were able to achieve a budget surplus (4.0 percent of GDP in 1990, 6.4 percent in 1991). The central bank continued its rather cautious monetary policy (increasing M2 by 3.7 percent in 1990, when the rate of inflation was 9.7 percent, and by 27.3 percent in 1991, when the rate of inflation was 56.6 percent). In the first weeks of 1990, we introduced a restrictive macroeconomic policy, which we considered a precondition for all liberalization.

Second, we launched a radical restructuring of government institutions, abolishing some and substantially changing the roles of others. In the first months of 1990, ministries ceased issuing “planning” directives because the enterprise sector had begun to be fully self-controlled and self-directed. When we came into office, that sector was not radically different from what it had been in the era of late communism, when the power of state-owned firms was already much greater than the power of central planners. This fact is still not fully understood in the comparative economic systems literature.

Third, elimination of the negative turnover tax – a radical measure introduced at the beginning of July 1990 – had a significant impact on the atmosphere in the country, its citizens, the prices of consumer goods, and the structure of consumer demand. Announced and explained in advance and accompanied by explicit social subsidies, this move changed hundreds or thousands of prices that had been considered untouchable in the previous 40 years and were therefore totally out of touch with economic reality. This signal was extremely strong. In January 1993 the entire turnover tax system was abandoned upon introduction of the value-added tax system.

Fourth, the government prepared the official announcement of the transformation project, the Scénár ekonomické reformy, in the summer of 1990, and Parliament approved it in September. It summarized our views at that time and announced further steps, including price and foreign trade liberalization, massive devaluation, and extensive privatization. Parliament supported the approach, declaring that “the scenario is a rational project for solving the difficult problems of our economy.“ It also approved our goal of creating a market economy.

Fifth, a few days before price and foreign trade liberalization, we devalued the Czechoslovak crown to more or less the level of the black market exchange rate. Our decision led to a very unpleasant dispute with the IMF, which wanted a deeper devaluation. We did not accept it – and rightly so. We succeeded in maintaining the same nominal exchange rate for another seven years (with the continuous appreciation of the real exchange rate).

This decision was the most difficult one made in the whole transformation era. Part of the dispute was about whether to devalue before or after price and foreign trade liberalization. We originally wanted to do so afterward but were convinced that ex ante devaluation was better. This decision proved to be well advised, on the condition that we chose a “good” exchange rate.

With all these large-scale changes, which were inevitable at that time, we were seeking a sufficiently flexible economy in transition. Therefore we originally wanted a flexible exchange rate. We quickly recognized the benefits of a fixed exchange rate, however, which provided a needed anchor when everything else was changing rapidly.

Sixth, on January 1, 1991, we liberalized prices and foreign trade. In the relatively stable macroeconomic environment (which reflected our restrictive monetary and fiscal policies and the relatively small macroeconomic imbalances inherited from the communist era), liberalization proved to be less dramatic than we expected and did not lead to the destabilizing chain reactions (price-price, price-wage, price–exchange rate spirals) we had feared.

The price (and wage) liberalization was general and comprehensive: 95 percent of prices were liberalized (albeit not fully in the housing and health care sectors). Prices rose by 25.8 percent the first month, 7.0 percent the second, 4.5 percent the third, and 1–2 percent over the next 60 months, excluding the month of the tax reform. Except in the year of price liberalization, the annual rate of inflation in the Czech Republic never exceeded 10 percent.

Finally, the most important part of the transformation process was privatization. The goal was to privatize the existing state-owned firms and not just allow new greenfield firms. We considered rapid privatization the best contribution to the much-needed restructuring of firms (we did not believe in the ability of the government to restructure the firms). Privatization of firms in the real economy could not wait for the privatization of banks. Because of the lack of domestic capital (which did not exist in the communist era) and the very limited number of serious potential foreign investors, firms had to be sold at prices lower than prices based on assets. This idea led to the concept of voucher privatization.

Transformation was not an exercise in applied economics. It was not carried out in a laboratory or a vacuum. It was heavily influenced by the everpresent political and social pressures, enhanced by sudden freedom (after decades of communism). Transformation was real life.

Selected Economic Data from the Era of Transformation

Economists are expected to be able to work with economic data, but they know (or should know) how problematic economic data inevitably are during a period of radical change of an entire economic system. Under communism Czechoslovakia had a functioning statistical system, but it was built on a methodology that was unsuited to the new environment. As a result, measuring the process and effects of transformation is rather complicated. One has to be very cautious, especially when making international comparisons, about both “real” economic data (such as GDP) and – perhaps even more – price data from the communist and postcommunist eras.

There has been serious discussion of this topic in the economic literature both abroad and in my country. The issue should not be underestimated. During the transformation, seeing the dominant trends was possible, whereas engaging in sophisticated economic fine-tuning was not. Part of the problem was that we were confronted with a constant revision of statistics, with repeated redefinitions of statistical indicators, different ways of defining the same phenomena, and so forth. The split of Czechoslovakia complicated these problems. Basing sophisticated macroeconometric models on such fuzzy data would not have worked.

What follows describes the broad trends and the main macroeconomic developments from 1990 to 1996.

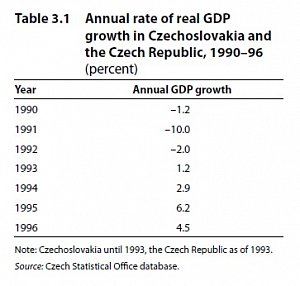

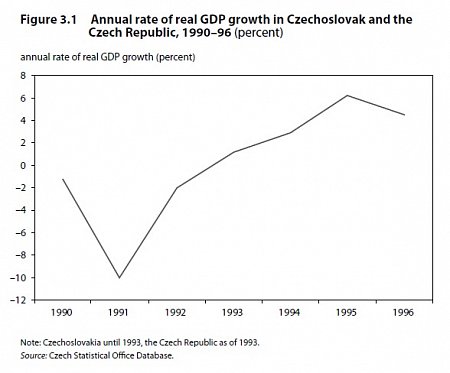

GDP

GDP declined in the first three years after the fall of communism, starting to grow in 1993 (table 3.1). There is no doubt that real output declined during the transformation – and we are convinced that it could not have been otherwise. The economy had to rid itself of its inefficient parts, which had become untenable under the new circumstances (as a result of different prices and exchange and interest rates and the sudden disappearance of major markets). We rejected (and keep rejecting) the politically motivated arguments of some of our critics who claimed we were going through a standard recession. We spoke then (and speak now) about a “transformation recession,” which we consider an inevitable, and in many respects healthy, development.

In the first three years after the end of communism, the Czech economy lost one-third of its industrial output, one-fourth of its agriculture, and onefifth of its GDP. This decline in output opened the way to economic recovery and growth in subsequent years. Growth followed a J-curve path (figure 3.1), which we had expected and announced in advance. It would have been a tragic political mistake to arouse unjustified expectations. However, the decline did not last long – the data for the next few years clearly reveal a positive turn.

Unemployment

We started the transformation process with no unemployment. Until 1996 the rate fluctuated around only 3 percent. Unemployment rose during the posttransformation recession of 1997–98, when GDP growth contracted (by –0.9 percent in 1997 and–0.2 percent in 1998).[7]

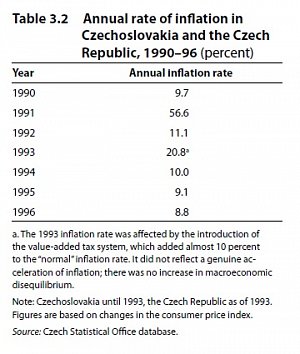

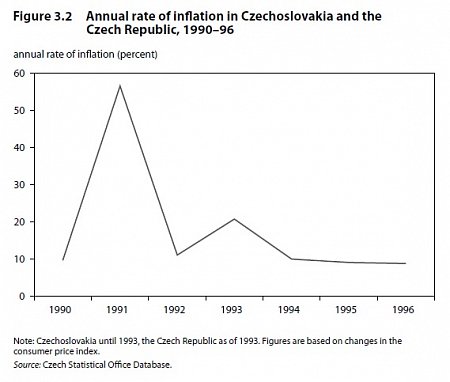

Inflation

The rate of inflation followed the expected course (table 3.2 and figure 3.2). The numbers look very high now, but at the time the country had the lowest inflation rate of all the transforming countries (except Hungary in 1991).

Unlike consumers in almost all other countries, Czech consumers did not lose all their savings. Inflation reached high levels only once, the year prices were liberalized (1991).

The rate of inflation in the early transformation era was not the result of lax macroeconomic policy. It was “transformation inflation,” related to the large-scale readjustments of all kinds of prices (and other nominal variables) that inevitably happened after four decades of frozen, administratively dictated prices. A more restrictive monetary policy would have killed the very fragile Czech economy, as it did in 1997–98.

Exchange Rate and Budget Balances

The exchange rate proved to be very stable under the circumstances, serving as an anchor for the whole economy. The currency was devalued three times in 1990 – In January, in October, and in December – as a precondition for price and foreign trade liberalization. The last devaluation, carried out in the last days of 1990, was proved correct because the nominal exchange rate stayed more or less constant for six or seven years, while the real exchange rate gradually rose. We introduced a fixed exchange rate system (not a crawling peg, as in Poland and Hungary) and kept it until 1997. On January 1, 1991, together with price and foreign trade liberalization, we introduced partial convertibility of the Czech crown.

The state budget developed quite positively, and we managed to avoid deficits most years (table 3.3). In fact, the first two postcommunist governments ran small budget surpluses, boosting confidence in the ability of the new government to handle the public finances.

Private Entrepreneurship

The transformation enabled the establishment of private entrepreneurship and private firms in our country. In the communist era Czechoslovakia had almost no private sector, which was unique even among communist countries. It had the smallest private sector of all the communist countries because of the aggressiveness of the communist takeover in February 1948 and the lack of reformist economic changes after the events of 1968. According to the World Bank, in 1989 the share of the private sector in GDP in Czechoslovakia was 1.5 percent – far lower than in East Germany (8.5 percent), Hungary (14 percent), or Poland (26 percent). The country had only 124,000 private entrepreneurs at the end of 1990. By contrast, it had 899,000 by the end of 1991, more than 1.2 million by the end of 1996, and more than 2.7 million by the end of 2013. By year end joint stock companies totaled 658 in 1990, 2,541 in 1991, 8,255 in 1996, and 25,057 in 2013. State firms numbered 3,505 in 1990 and only 694 in 1996. These data are compelling.

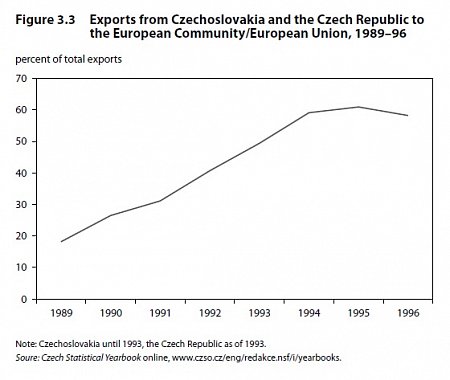

The main vehicle for microeconomic change was privatization and its preparation. Foreign trade went through a radical geographic reorientation during the first transformation years. In 1989 the share of other centrally planned economies in Czech foreign trade turnover was 61 percent. By 1996 only 30 percent of the country’s foreign trade was with transition economies, whereas 64 percent was with developed market economies (figure 3.3).

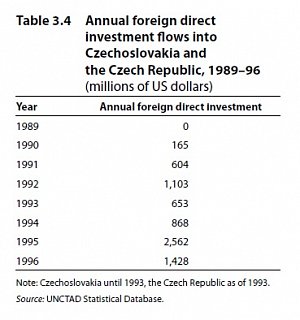

Inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) also contributed to the development of the corporate sector. FDI rose from zero in 1989 to almost $2.6 billion in 1995 (table 3.4 and figure 3.4).

Privatization and Its Czech Peculiarity

From the very beginning, we Czech reformers knew that we had to privatize the economy we had inherited as quickly as possible. We had many reasons to believe that the speed of privatization was an asset, not a liability. We did not want to leave the suddenly “parentless” firms uncontrolled. Nor did we want them to become objects of spontaneous privatization by former managers appointed by the communist rulers. We were not interested in the size of privatization proceeds, because our goals were different. Our aim was structural change – to privatize the whole economy.

We were fully aware of the fundamental difference between privatizing a few individual firms in a “normal” capitalist market economy and privatizing a whole economy. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher successfully privatized individual British firms in the 1980s. The Central and East European reformers privatized entire economies a decade later. In the first case, the privatization proceeds were an important source of revenue for the government, and it was meaningful to maximize them. In the second case, the size of the privatization proceeds was not crucial. The main goal of reformers was to change the economic system. In Czechoslovakia we were not able to prepare thousands of firms for privatization. Our main imperative was speed. We wanted to maintain the momentum and not lose the most precious asset available: the transformation drive and spirit.

We agree with all our critics that when privatizing individual firms, moving very quickly reduces the privatization proceeds. In our case, however, we believed that the slower the process, the greater would be the social and economic costs of privatization. We did not want to leave our to-be-privatized firms in preprivatization limbo, during which they would rapidly lose value.

Our approach was based on several principles that we had to explain, defend, and push through both at home and, with even more difficulty, in our dealings with academic advisors from abroad, missions of international organizations, investment bankers, and potential investors. The principles included the following:

- Privatizing the whole economy is a costly process. It should be based on minimizing costs rather than maximizing revenues (and fees for foreign consultants).

- The goal of our wholesale privatization was to increase the efficiency not of particular firms but of the economy as a whole.

- Privatizing the whole economy is a way to open the economy to new entrepreneurs as well as to investments in start-ups or greenfield firms. We believed it was neither useful nor possible to try to find “optimal” owners. On the contrary, it was vital to get the privatization done so that the market rather than the state could sort out who the best owners really were.

- Foreign investors do not deserve privileges; they should be treated like anyone else. We knew that foreign capital never comes into a country to help, as was often proclaimed in a purely propagandistic way. Foreign investors were welcome, but it was never accepted in the Czech Republic that they should play a pivotal role.

- The institutional framework of a full-fledged market economy cannot be built ex ante. It has to be an outcome (not a prerequisite) of transformation and privatization.

- Even the best imaginable privatization methods could not have saved all of the state-owned firms we inherited. Indeed, the market found most of these firms inefficient and untenable. It was also technically impossible to determine the true value of these firms without the information delivered by the market.

To all the ill-informed commentators, we have to repeat even now that our task was to privatize thousands of enterprises. We could not restructure them first. We did not want to give the task of restructuring to the state, which would have radically enhanced its role. Rather, we believed that the new private owners had to carry out the restructuring.

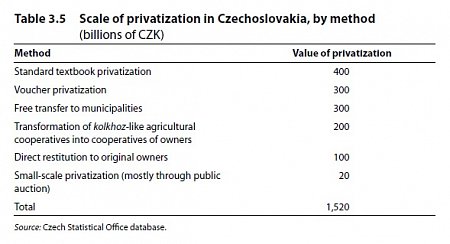

Based on all these arguments, we came to the conclusion that we had to use a mixture of privatization methods, some of them very nonstandard. Foreign observers continue to focus on our voucher privatization. This method played an important but not dominant role, accounting for less than a quarter of all privatization (table 3.5).

The debate abroad about the size and the role of voucher privatization and its substance (and technology) is often very misleading. We are still very proud of “inventing” this method – or at least how to apply this idea.

Under our system firms were first converted into joint stock companies whose shares were privatized.[8] Firms had to prepare their own privatization projects, suggesting their own choice of privatization method (any other economic agent could present a competing project). There was no government dictate in this respect. We conducted no new valuations of firms. The shares of privatized firms represented their book values, which were administratively set in the past.

All Czech citizens had a chance to participate in this process, as long as they paid a modest registration fee of CZK 1,000 ($30–$40, or an average weekly salary at the time). The 8.5 million citizens who participated received 8.5 billion “investment points,” which they were able to use in the subsequent bidding to buy privatized shares. Citizens could invest their investment points directly or place them in the newly established investment privatization funds.

Based on supply and demand, a highly sophisticated pricing method using modern computer technology determined the values of auctioned shares in investment points (not Czech crowns). It took five bidding rounds to sell all the shares, spend all the investment points, and establish the “equilibrium” values of the auctioned shares. The unexpected result – the outcome of the voluntary decisions of Czech citizens – was that the investment privatization funds acquired 66 percent of the shares. The remaining 34 percent remained in the hands of individual investors. Immediately after the auctions, the new owners began to trade the shares on the secondary market. This process launched the badly needed restructuring process.

We are convinced that the privatization process in the Czech Republic was a success. Citizens received their first lessons in capitalism, and after decades of “public” (which means no one’s) ownership, capitalist institutions and firms found themselves with real owners. Inevitably, the process had casualties and imposed socially negative side effects. But these effects were the price to be paid for transformation and privatization – or to put it differently, for communism. Like everything in life, this process undoubtedly could have been better. But it was not an exercise in applied economics; it was a real-life operation. Privatization and the whole transformation could not have been costless. It would have taken a miracle to rid the country of communism more easily.

Concluding Remarks

Let me end with three major conclusions about the postcommunist economic transition, not only in the Czech Republic but also in general. First, the economists turned politicians who implemented reform following the fall of communism in Central and East European countries knew they had to attempt to change the entire economic, political, and social systems of their countries. They wanted to accomplish a fundamental and total systemic change. Some of them understood quite well that partial, piecemeal reforms would not do. They realized that they had to put together a critical mass of steps, measures, and changes at one moment.

Knowing that the changes would not be painless or costless (however necessary and inevitable they were), reformers had to convince the people that they were serious, that they were seeking to make substantial changes, that they would not try to maximize their number of years in office by making only superficial, easy changes. They also wanted to achieve real change – even in the face of all the attempts by status quo defenders to block change and the powerful inertia of institutions and people’s behavior.

Second, successful economic transformation requires mixing all the necessary ingredients together without leaving any of them out. I want to be well understood. I am not talking about perfection, about a 5,000-page ex ante blueprint of comprehensive reforms implemented after years of preparation (despite the growing impatience of suddenly free people). I am not talking about the would-be merciful, friendly to everyone, Joseph Stiglitz–style gradualism, which is a phony and deceitful nickname for doing nothing. I am speaking about a practical, meaningful, flexible, adaptable, realistic project.

It is difficult to put together all the ingredients in theory because reformers are dealing with a multidimensional system and with real people, not pawns in a chess game. Reform is much more difficult to implement in practice than in theory. Before the fall of communism, people like me studied all kinds of theories about the “optimal sequencing of reform measures.” My experience tells me that anything like optimal sequencing is possible only in textbooks, not in practice. Detailed masterminding and fine-tuning of systemic changes are impossible.

Some basic rules do exist, however. I would include among them the following:

- A critical mass of reform measures should be adopted at the very beginning.

- Basic macroeconomic equilibrium should be achieved in order to avoid the destructive effects of high inflation.

- Prices should be liberalized only after a reasonable degree of macroeconomic stability has been achieved.

- Prices and foreign trade should be liberalized simultaneously.

- Transformation has no meaning without early, rapid, and widespread privatization. Privatization must be carried out without waiting for the much-needed restructuring of firms or the emergence of domestic capital. Nonstandard concepts, such as voucher privatization, are therefore inevitable.

- The institutional framework of the market economy is an important contributor to the success of reforms, but institution building is an endless task. It is impossible to wait for perfect institutions. It would be a mistake to delay deregulation, liberalization, desubsidization, privatization, and other reform measures while waiting for fully developed institutions to emerge.

Third, a precondition for the success of the transition was the ability to explain the process, including its inevitable costs, to the people. Doing so was probably our most difficult task. People have to believe in the transformation process; they have to become co-players, providing political support.

References

Czech Statistical Office. Various years. Czech Statistical Yearbook. Prague. http://www.czso.cz/eng/ redakce.nsf/i/statistical_yearbooks_of_the_czech_republic.

Klaus, V. 2000. Three Years after the Currency Crisis: A Recapitulation of Events and How They Are Linked, to Make Sure They Do Not Fade from Memory. SVU Congress, Washington, August 10. Available at www.klaus.cz/clanky/488.

Klaus, V. 2009. Kde zacíná zítrek? [Where Tomorrow Begins?]. Prague: Knižní klub. [Also available in Bulgarian, Polish, and Russian.] Klaus, V. 2013a. My, Evropa a svet. Prague: Fragment.

Klaus, V. 2013b. The Post-Communist Transition Should Not Be Misinterpreted. Economic Affairs 33, no. 3 (October): 386–88. Available at www.klaus.cz/clanky/3468.

Klaus, V. 2014a. The Carefully Organized Separation of Czechoslovakia as an Example How to Peacefully Solve a Nation State Problem. Opening lecture at the conference “Qualified Autonomy and Federalism versus Secession in the EU and Its Member States,” Esterházy Palace, Eisenstadt, Austria, February 26. Available at www.klaus.cz/clanky/3530.

Klaus, V. 2014b. Fundamental Systemic Change Is Not an Exercise in Applied Economics. Leontief Centre, St. Petersburg, Russia, February 15. Available at www. klaus.cz/clanky/3519.

[1] This chapter reflects my personal views, prejudices, and, of course, mistakes and misunderstandings. I do believe, however, that I express something specifically Czech – something fairly representative of the views in my country at the time of the postcommunist transition.

[2] Transition refers to the postcommunist era of systemic change. Transformation refers to the efforts to carry out that change.

[3] The dispute with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) mission in December 1990 about the choice of exchange rate is a well-known example.

[4] Our esteemed colleague Yegor Gaidar made this now-famous statement in Warsaw in November 1999.

[5] Such ideas persist, supported more and more by official EU attitudes and the ideology of Europeism. But that is a different topic.

[6] Use of the term shock therapy is an intentional political attack used by people such as Joseph Stiglitz.

[7] The unnecessarily restrictive monetary policy the central bank introduced in the second half of 1996 caused this recession (see Klaus 2000, 2013b).

[8] In some cases, only parts of a company were privatized.

Václav Klaus, "Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic - The Spirit and Main Contours of the Postcommunist Transformation", The Great Rebirth - Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington D.C., November 2014.

- hlavní stránka

- životopis

- tisková sdělení

- fotogalerie

- Články a eseje

- Ekonomické texty

- Projevy a vystoupení

- Rozhovory

- Dokumenty

- Co Klaus neřekl

- Excerpta z četby

- Jinýma očima

- Komentáře IVK

- zajímavé odkazy

- English Pages

- Deutsche Seiten

- Pagine Italiane

- Pages Françaises

- Русский Сайт

- Polskie Strony

- kalendář

- knihy

- RSS

Copyright © 2010, Václav Klaus. Všechna práva vyhrazena. Bez předchozího písemného souhlasu není dovoleno další publikování, distribuce nebo tisk materiálů zveřejněných na tomto serveru.