Nejnovější

- Václav Klaus na semináři IVK: Co znamená vítězství Donalda Trumpa

- Václav Klaus v diskusním pořadu slovenské televize RTVS: Jaká změna přichází s Trumpem?

- Notes for Montenegro: A World Order Under Threat. Is There Any Chance to Change It?

- Václav Klaus v 59. díle pořadu XTV: Pane prezidente!

- Institut Václava Klause obdržel Cenu za svobodu projevu

Nejčtenější

- Václav Klaus pro MF Dnes: Mnozí se už stačili „prekabátit“

- Jiří Weigl: Česká politika začíná mít znovu problém

- Václav Klaus: Jdeme od listopadu 1989 stále kupředu? Pohled jednoho z aktérů tehdejší doby

- Jan Fiala: Včerejší lesk a dnešní bída progresivismu

- Václav Klaus v 59. díle pořadu XTV: Pane prezidente!

Hlavní strana » English Pages » Promoting Financial Stability…

Promoting Financial Stability in the Transition Economies of Central and Eastern Europe

English Pages, 29. 8. 1997

It is a great pleasure to be here after seven years, to have the chance to meet old friends and to report both about non-negligible and undeniable positive results which have been achieved in the transition economies of Central and Eastern Europe between my two visits to Jackson Hole, and about not less undeniable problems connected with such a unique historical manouvre. The seven years time span makes it possible to base our discussion on the existence and understanding of many important similarities among the transforming countries which are, however, sometimes difficult to discover behind evident differences. I will use mostly Czech data and Czech experience but my ambition is to at least implicitly generalize and outline broader tendencies or principles.

I happened to be here in 1990, at the moment of overall optimistic forecasts and expectations and of preparations towards radical moves forward in the near future. As we see it now, the future was not identical for all the countries in question. It is not difficult to say why. Some countries spent that critical period in non-productive political debates without the ability to formulate clear visions and transformation strategies and because of that, they made costly consessions to all, loosened fiscal and monetary controls, intensified economic imbalances inherited from the communist past and by doing it further destabilized the economy as a whole. It could have been expected that to liberalize prices and foreign trade in such an unstable situation meant to bring about rapid and persistent inflation, sharp economic decline, huge shifts in income and wealth distribution as well as the deterioration of living conditions of large segments of the population. As a consequence of it the vital reform measures were blocked or postphoned to a much less favorable situation.

Other countries, however, used the preparatory stage for generating essential preconditions for the implementation of subsequent radical reforms. When I was here in 1990, my talk (1) was mostly devoted to the discussion of these preconditions. I stressed the importance of restrictive macroeconomic policies - e. g. cautious monetary policies and surplus state budgets - as the only way how to escape from falling into what I used to call the „reform trap“.

The history proved that the implementation of such a restrictive macropolicy, together with simultaneous merciless devaluation, made the opening of domestic and foreign markets possible at relatively low costs for society. I will briefly discuss the situation in both the internal and external sphere in the last years as an argument in this respect.

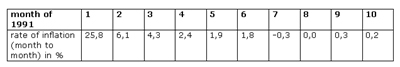

The rate of inflation after price liberalization moved in my country very rapidly to a more or less acceptable level, as can be seen from the following table (price liberalization was done January 1, 1991):

I agree with economists who argue that to reduce it further and faster would have been very costly. With the exception of the deliberate price shift in January 1993 (as a result of the introduction of the value-added tax system), the seasonally-adjusted monthly inflation did not exceed one percent level very often and was always below 2%. (The synergic effect of currency depreciation, of a radical shift in deregulation of rents and energy prices, and of floods, in July 1997 is, however, a different story.)

The annual rate of inflation has been since 1992 rather stubborn at about 10% level - with the lowest annual rate achieved this April at 6,3%. The explanation of the relative persistency of such an inflation rate cannot be in my view explained by monetary or macroeconomic factors only or dominantly, because there were important structural factors (and impulses) at play, connected with the extraordinary high frequency of changes in relative prices. It was an integral and necessary part of the restructuring of both nominal and real variables in the transforming economy.

My conclusion is that the inflation slowdown to such a moderate level could have been arrived at provided cautious macroeconomic policies were pursued with sufficient consistency.

It was more difficult to achieve external equlibrium. In the first stage, in the moment of substantial economic decline (1991-1993) - which was caused by an unavoidable transformation-shakeoff of non-viable economic activities associated with the old economic system, not by an excessive macroeconomic restriction (as was sometimes suggested) - the domestic aggregate demand did not reach the level of the aggregate supply. There was, evidently, a shortage of domestic demand. As a result of it, exports were bigger than imports which - together with strong capital inflows - preserved balance of payments equilibrium and led to the growing stock of hard currency reserves.

In the second stage, in the moment of economic recovery (1994-1996), rapid growth of investment (and very high investment ratio, exceeding significantly domestic saving ratio), together with our rather innocent opening of the whole economy towards more protected trade partners, produced a radically different outcome. The aggregate demand exceeded the domestic aggregate supply and imports exceeded exports. At first balance of trade, then the current account of the balance of payments and finally the capital account turned into deficit. As is well-known, the final stage of the drama was played by massive speculation against the Czech crown in May 1997, by its unintended depreciation and by its free floating since that time.

This recent accident was undoubtedly the most important phenomenon of instability in our whole post-communist era, of financial instability in a broader sense. We have to admit that we did not succeed in finding an easy and straightforward way how to prevent it.

Was it possible to avoid it at all? It is too early to give a final answer but I have some reservations about it - given all political and economic domestic and international constraints - and will therefore try here, today to briefly discuss some relevant arguments in this respect as I see them.

1. The exchange rate regime and the exchange rate level

The collaps of communism „happened“ in the moment when the economic profession believed in fixed exchange rates and in the advantage of anchoring the economy by means of one fixed point - especially in a situation when all other variables undergo large changes and fluctuations. I have to confess that I was originally afraid of introducing such a rigid regime but the first impressions were positive because we succeeded in choosing an exchange rate which functioned well for very long 76 months. By sufficiently devaluating the crown on the eve of price liberalization we formed something what I later called the „transformation cushion“. The exchange rate cushion (as well as the parallel wage cushion) appeared to be crucial for the whole subsequent transformation process. The inflation differential was in our case not as big as in some other transforming countries but the appreciation in real terms reached in 76 months almost 80 %, which was too much. Although we have been constantly checking the remaining thickness of our exchange rate cushion, as we see it now, we - probably in the middle of 1996 - missed the most suitable moment for the abolition of the fixed exchange rate regime. The question is, however, whether the subsequent movements of the rate of exchange would have been less dramatic than they were in reality in recent months. The vulnerability of an emerging market economy is in this respect very high and, probably, unavoidable.

The tentative lesson No. 1: fixed exchange rate regime should not last too long.

2. Investment - savings imbalance

The economic recovery has been - since 1993 - relatively rapid (in European terms). It was pulled by strong investment demand (with only modestly growing private consumption and exports and with stagnating or declining government expeditures).

The rapid growth of investments seems to be unavoidable. The problem is in the structure of investments. The overwhelming feeling of obsolescence of infrastructure (of all kinds) after four decades of communism together with overambitious „green“ attempts to rapidly undo the well-documented environmental damage, caused by the absence of private property and a market economy led to an extremely high investment ratio (33% in 1996). Only a smaller part of investments was „productive“ in the narrow sense, and contributed to industrial restructuring and modernization. To reconcile strong investment demand with domestic savings was almost impossible because we did not succeed in creating the atmosphere of „belt-tightening“ as the only way how to overcome the heavy burden of the communist heritage. The problem is clear, the solution not.

The tentative lesson No. 2: it is necessary to restrain the „catching-up“ ambitions and the impatience of society as much as possible.

3. Wage - Productivity Nexus and the Degree of Competitiveness

Price liberalization, accompanyied with rather restrictive macroeconomic policy, generated another significant transformation phenomenon - the wage cushion, because wages went up much slower than prices. As a result of it, real wages could - for some time - grow faster than GDP or productivity without undermining competitiveness of the whole economy. It gave our enterprise sector a breathing time which only a part of it effectively used for radical restructuring. We were, however, not able to prolong the process of emptying the cushion. The government could not control the private sector and was not able (or strong enough) to block the growth of salaries and wages in the public sector. The relatively rapid growth of wages in the private sector was made possible by soft (or unsufficiently hard) granting of credits by the banking sector and by the slow process of bankrupcies on one hand and by strong demand for labor and very low unemployment on the other. Non of these factors could be directly controlled by the government.

The tentative lesson No. 3: The rate of growth of wages is not a „free“ policy variable (as is sometimes implicitly suggested by external observers and advisors).

4. Quality of Markets, Economic Strength and High Degree of Foreign Trade Liberalization

With the benefit of hindsight it can be argued that the scope and rapidity with which former communist countries opened their economies and adopted currency convertibility was much larger and faster than in similar historical moments in the past. As we all know, it took much longer time to do it in Western Europe and Japan after the war. And, in addition to it, it was done in the situation of high degree of globalization of world markets and in the situation of enormous structural shifts in the financial system itself as well as in the moment of sophisticated protectionism in developed countries (in Europe especially). We do not know whether it was a blessing or a curse. The entry of strong firms from developed countries into our unprotected markets was much easier than the entry of our technologically, financially and organizationally much weaker firms into their „occupied“ and protected markets. When I dare to say that I do not mean it as an advocacy of the policy of sheltering the markets of young, unmature industries. I use it, however, as a part of my explanation of our trade deficit.

The tentative lesson No. 4: A small, open, industrial ex-communist economy pays - in the short run - more for trade and currency liberalization than a big, less opened and less industrial economy.

5. Fiscal and Monetary Policy Mix

Until very recently, we succeded in having either surplus or balanced budgets and a relatively cautious monetary policy (with unknown shifts in the velocity of money (2)).

It seems natural to argue that the growing external imbalance required some degree of macroeconomic tightening. But the politicians had the feeling that to have budgets without deficits for seven consecutive years is the maximum they could offer. To criticize them (in this respect) seems to me inappropriate.

Some degree of money supply deceleration was necessary as well. It did happen in our case but to slow down the annual rate of money supply growth from 18-20% (in the first half of 1996) to 10-12% (in the second half of 1996) and to 6-7% (in the first half of 1997) by the not preannounced step of the Central Bank was something which - at least - asks for a discussion of the real meaning of the central bank independence. It had - as expected - faster impact upon aggregate supply than demand and contributed to the apparent economic slowdown (if not decline), to unexpected budgetary problems (on the income side), to heavy political conflicts and uncertainty and, finally, to the increased financial instability as well as to the recent currency weakness.

The tentative lesson No. 5: To make sharp changes in monetary policy proves to be very dangerous.

6. Fragility of Financial Institutions

Financial institutions (banks and other financial intermediaries) in the post-communist countries have many „childhood“ problems and cannot be relied upon contributing sufficiently to the stability of the whole economy. Whether we wanted it or not, the banks and other financial institutions were an integral part of the transformation process and could not get the status of a „clean“ outsider as was sometimes suggested. They inherited difficult loan portfolios, with their transformation and privatization involvements they added to it not much less contraversial assets, they have complicated ownership structures, etc. The masterminding of their evolution is, however, impossible.

There is no doubt that the fragility of our financial markets was an additional complicating factor. Their lack of transparency and stability contributed to the slowdown of capital inflows and aggreviated thus the balance of payments problem. The only relevant question is what could have been done ex ante.

Capital markets are different from ordinary markets and they probably need more government intervention or regulation than ordinary markets. The problem is how to intervene, how to regulate them without constraining them unnecessarily and without expecting too much from the regulator who is a human being as the rest of us (with his well-defined utility function which he tries to maximize) and who operates in a world of intensive rent-seeking and in a world of the well-known fallacies of regulation. I am not very optimistic about regulation in general and about regulation of capital markets in particular (3).

Our capital market has grown much faster than anyone expected, especially when we gave it a strong accelerating impulse by our voucher privatization. In the early nineties I fully shared Joseph Stiglitz’s view (4) that „to a large extent, equity markets are an interesting and amusing sideshow, but they are not at the heart of the action“ (p. 32) because we started our economic transformation with heavy reliance on the banking system. While trying to expand it rapidly we probably underestimated the need to impose sufficiently high capital requirements and, at the same time, we did not succeed in strictly dividing the financial and production sectors of the economy. We - more or less - accepted the German (or continental) type of banking with its strong inter-relationships between banks and firms in the production sector. We see many problems with it now but I am not sure we could have started differently.

With the spontaneous evolution of our financial markets, with literally millions of shareholders and hundreds of investment companies and funds, mostly as a by-product of voucher privatization, we failed in generating the sufficient degree of information about the financial position of individual firms. It is connected with the lack of intensity of transactions in our today’s markets which is unavoidable (the markets are shallow and, therefore, not efficient), and it may be - at the same time - the result of delayed legislative measures on the side of the government.

The question of lags in public policy is, however, not simple. Joseph Stiglitz mentioned in his study that „much of the return in capital market consists of rent-seeking“ (p. 15) and I have to admit that in the past some of us did not immediately believe all the critics of our capital markets because they usually played their own card and did not take into consideration the existing stage of the evolution of the whole economic system. Their criticism was very often indistinguishable from the complaints of those who just occured a loss by making a wrong investment.

The main problem is not the legislation itself. The problem is law enforcement, efficient control and rational regulation. There is a clear need to speed up the judicial procedures and to establish specialized financial courts dealing with bankruptcies and matters related to capital markets.

The tentative lesson No. 6: The capital markets begin to function faster than you expect and before you try to regulate them.

To conclude, I have to repeat that my answers to the existing problems are tentative but I hope that they clearly suggest that my doubts about the possibility of a smooth and stable transition path in politically and socially difficult, but highly democratic, pluralistic and open economies and societies of Central and Eastern Europe continue to exist because we are not in a „brave new world“ of perfect markets and of perfect governments. It remains our task, however, to minimize the inevitable instability.

Václav Klaus, 21st Annual Economic Symposium on Policy Issues, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, 29 August 1997

1 - Policy Dilemmas of Eastern European Reforms: Notes of an Insider. In: Central Banking Issues in Emerging Market-Oriented Economies (symposium sponsored by The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 23-25, 1990).

2 - See my „Creating a Stable Monetary Order“, in „The Rebirth of Liberty in the Heart of Europe, CATO Institute, Washington, D.C., 1997

3 - Similar arguments were raised by the President of the FRB of KC T. M. Hoenig in his recent speech, published in the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, March, 1997

4 - „Financial Systems for Eastern Europe’s Emerging Democracies“, Joseph Stiglitz, 1993. Published by the International Center for Economic Growth, San Francisco, Occasional Paper, No. 38.

- hlavní stránka

- životopis

- tisková sdělení

- fotogalerie

- Články a eseje

- Ekonomické texty

- Projevy a vystoupení

- Rozhovory

- Dokumenty

- Co Klaus neřekl

- Excerpta z četby

- Jinýma očima

- Komentáře IVK

- zajímavé odkazy

- English Pages

- Deutsche Seiten

- Pagine Italiane

- Pages Françaises

- Русский Сайт

- Polskie Strony

- kalendář

- knihy

- RSS

Copyright © 2010, Václav Klaus. Všechna práva vyhrazena. Bez předchozího písemného souhlasu není dovoleno další publikování, distribuce nebo tisk materiálů zveřejněných na tomto serveru.